A friend sent me a paper about the Calcutta Botanic Garden (now called Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden) and I found the biggest beef between two people whose unstable relationship reflected the friction between empire and science. I’ll add some excerpts here.

About the Calcutta Botanic Garden:

The Company’s Botanic Garden was established at Sibpur near Calcutta in 1787 by Colonel Robert Kyd. While the new garden included a teak plantation to support ship-building and repair, its primary function lay in the introduction and acclimatisation of exotic plants for dissemination across the Company’s Indian possessions. Aside from the commercial imperative, Kyd recognized a strong humanitarian justification for the garden: it was hoped that the promotion of new crop varieties along with improved techniques and technologies of agriculture would serve to avert the “dreadful visitations” of what Kyd termed “the greatest of all calamities, that desolation [caused by] Famine and Subsequent Pestilence” But it was under the superintendentship of William Roxburgh, a true disciple of natural history, that the garden found its place as a premier scientific institution. Recognising a utilitarian role for botanical science, the documentation of India’s flora was heavily promoted by Roxburgh after he succeeded Kyd as Superintendent in 1793.

In the late eighteenth-century scientific investigations into the Company’s expanding sub-continental possessions were carried out by an array of gentlemen amateurs, company surgeons, surveyors and travellers of varying degrees of official status. Whether employed directly by the East India Company, or submitting their findings to various learned societies either in India or Europe, these men offered report after report on the vast array of new phenomena that they encountered. The wide sweep of their intellectual interests was efficiently summarized by the motto of the Asiatic Society of Bengal founded by Sir William Jones in 1783: “Man and Nature; whatever is performed by the one or produced by the other”

Far from being a one-sided, top-down affair, science in late eighteenth-century India reflected the practices of trade on which the Company’s fortunes were founded. Though not an equal relationship, the collaborative role of Indian intermediaries, interpreters, artists and assistants was of vital importance.

In the 20 years after the foundation of the Botanic Garden, the East India Company went from being a trading organisation (albeit one which already controlled a significant amount of territory) to being the pre-eminent political and military power in south Asia.

This transformation from trade to governance would stimulate wide-ranging changes in the role and practice of science in the subcontinent.

NATHANIEL WALLICH

As the Danish son of a Jewish merchant, Wallich would be expected to struggle to gain acceptance among the elite of Calcutta society. His status as an outsider may explain the policy of opening up the garden to visitors. During Wallich’s tenure the Calcutta Botanic Garden became a public pleasure ground – an elegant space for the instruction and entertainment of the growing European population of the capital of British India, a place to picnic and to promenade. Wallich’s efforts to please his superiors were often in sharp contrast to his argumentative nature and the harsh treatment he could meet out to employees of the garden. When Wallich was afflicted by serious illness in 1842 his opponents were waiting to take their chance.

WILLIAM GRIFFITH

William Griffith was considered “the greatest botanist that ever set foot in India”.

Not only was Griffith the possessor of formidable intellectual and artistic talent, but he was also gifted with great stamina and energy. Over the 13 years after his arrival in Madras in 1832, his tours of botanical discovery took him “from the banks of the Helmund and Oxus to the Straits of Malacca; he was rumoured to have been assassinated in Burma and managed to conduct botanical investigations in Afghanistan while travelling alongside the invading Army of the Indus. His collection of “not under” 9,000 species from Assam, Bhutan, Bengal, Sind, Afghanistan, Burma and the Malay Peninsula represented “by far the largest number ever obtained by individual exertions”.

THE FEUD

But if Griffith was the most exceptional botanist in India in this period, he shared an uneasy relationship with Nathaniel Wallich – the most powerful and well connected. Friction developed as Wallich allegedly became jealous over Griffith’s greater ability as a plant collector. According to J. McClelland, Wallich accused Griffith of concealing some of the plants that he had found and insisted that their collective efforts should be brought together in a single official collection. Griffith confided in his private journal that Wallich was a compound of “weakness, prejudice and vanity”: it was, he concluded “utterly impossible to pull well with such a man”.

The only thing that Wallich wanted more than to retire to Europe was to qualify for a full Company pension: and to do that he had to remain in India for just a few more years. In Wallich’s absence, and much against his wishes, Griffith was appointed Acting Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden. He accused Wallich of having left the garden in a neglected, unorganized state, and immediately seized the opportunity to make changes he saw as long-overdue.

A shift towards greater empiricism and direct observation required that objects be abstracted away from the wider environmental and social contexts in which they existed. Significantly, in the colonial setting the separation of observer and subject reinforced a growing racial divide with the practice of science itself increasingly used as an ideological justification for colonial rule.

Wild nature would no longer be dominant in India: intervention in the form of railways and irrigation works, vaccination programmes, and even hunting expeditions could be presented as serving to tame nature and promote its productive virtues.

REORDERING THE GARDEN

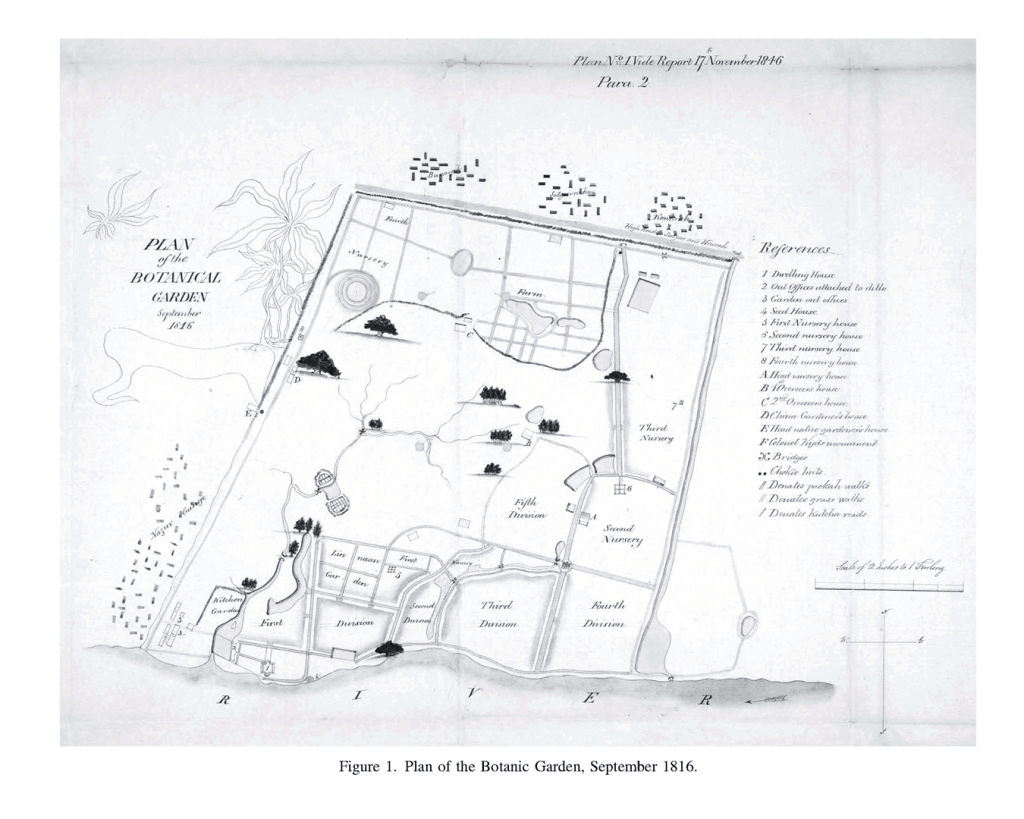

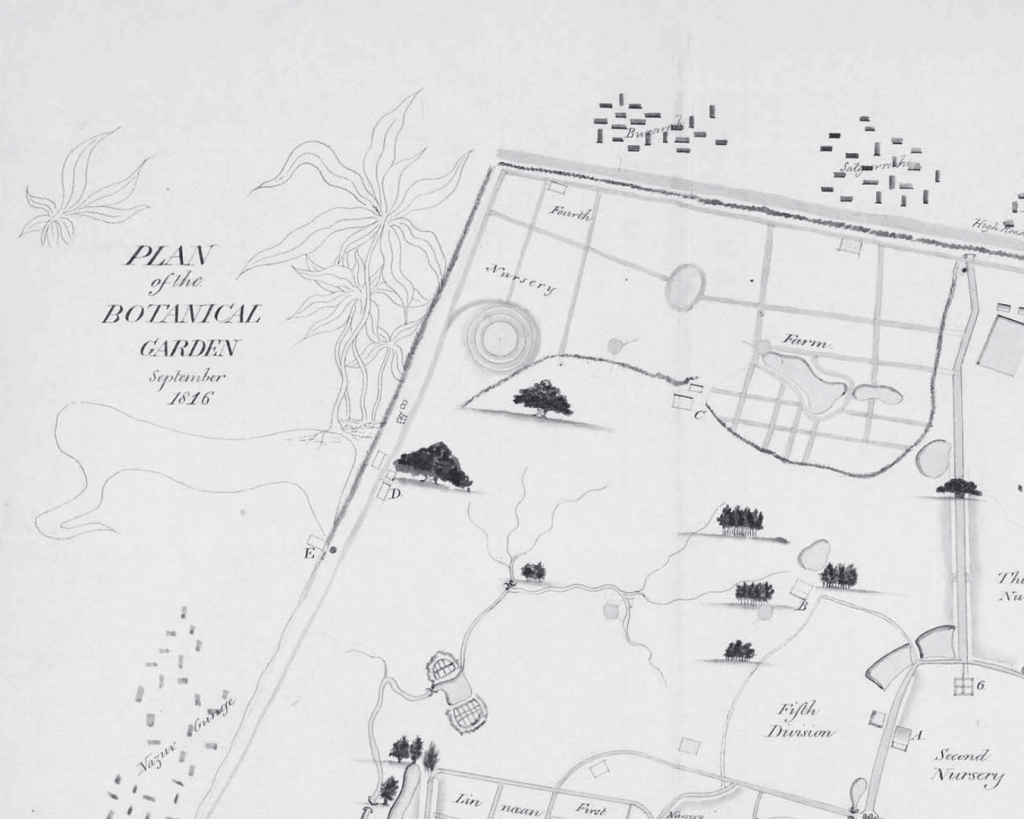

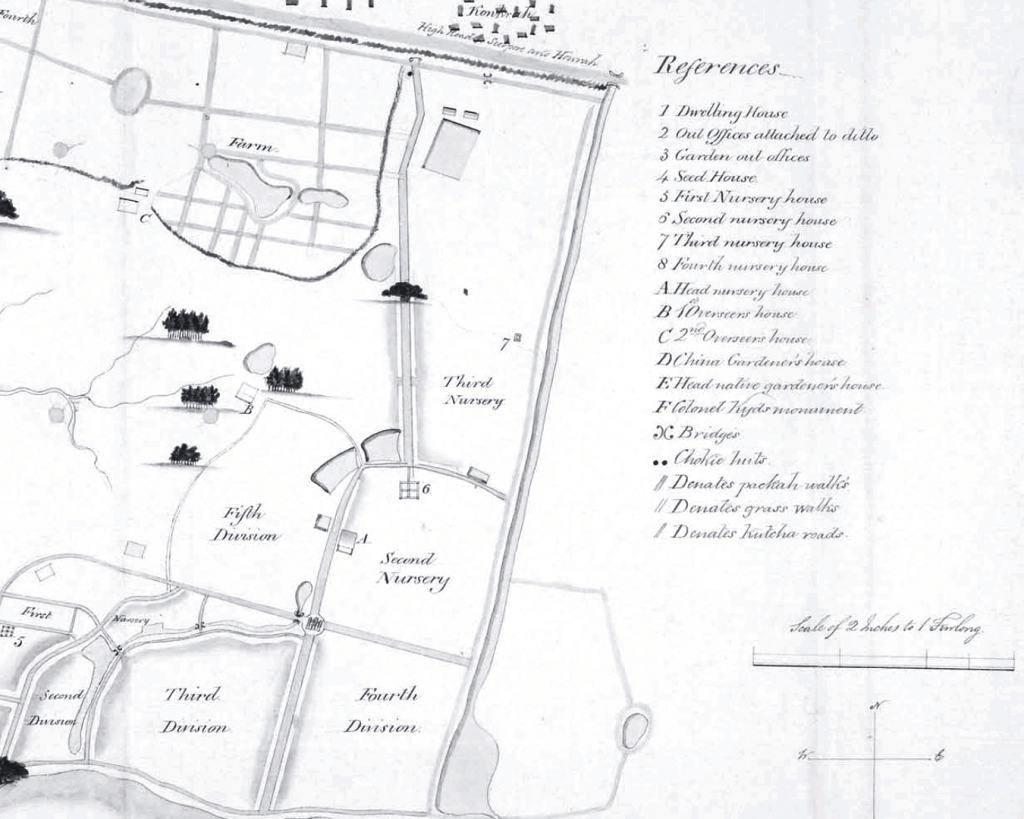

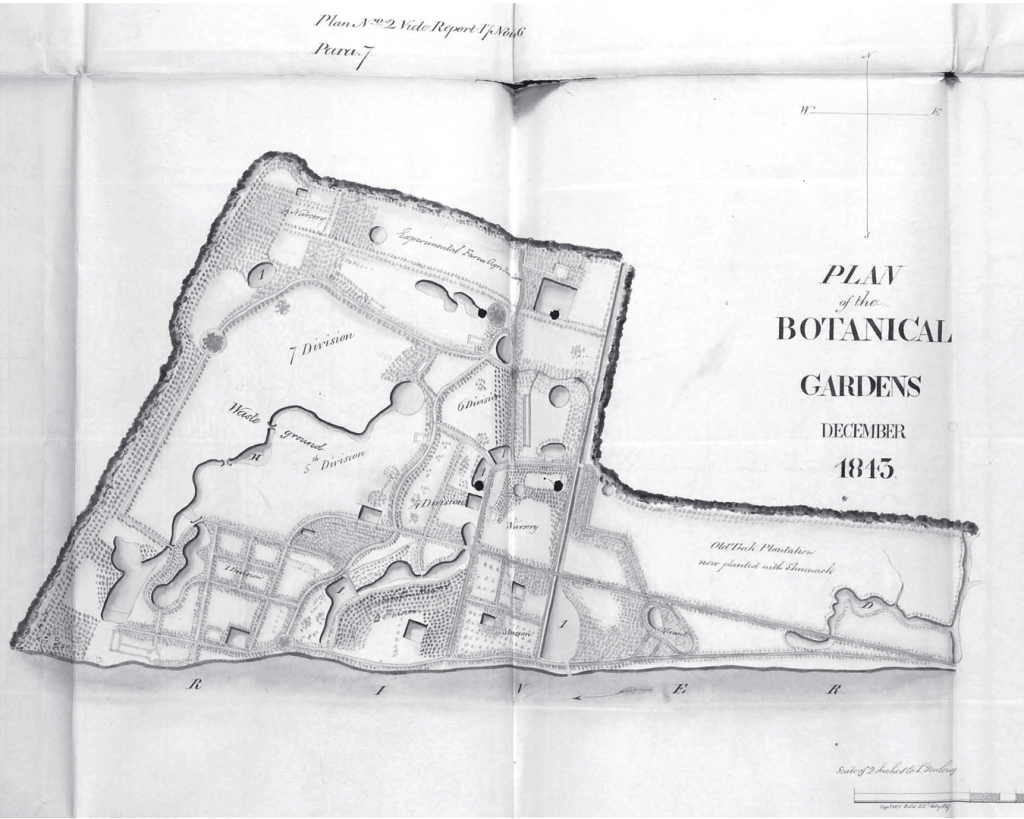

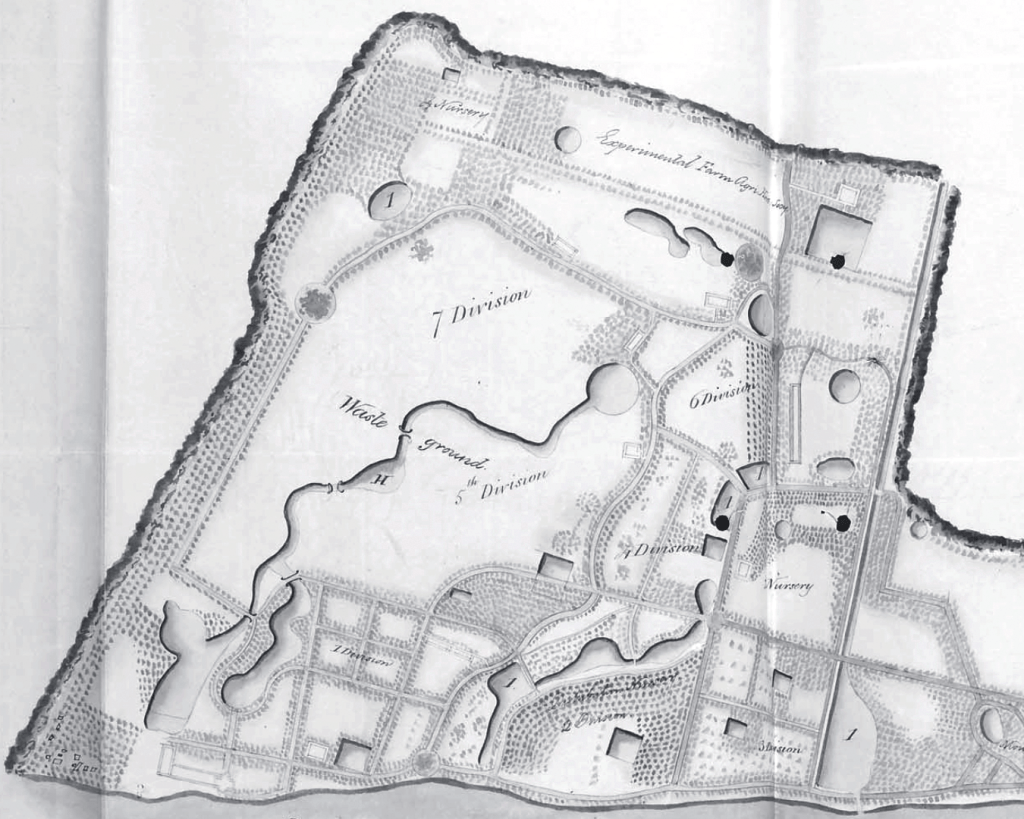

Drawn-up on the orders of Griffith’s great ally John McClelland, the timing of the three maps described here is quite deliberate. The first map shows the garden at Calcutta as it was immediately prior to Wallich assuming charge.

The second documents the garden as Griffith found it when he took up the post of acting Superintendent. A comparison of the two maps is intended to illustrate McClelland’s view that, over nearly 30 years under Wallich’s charge, “no material change would seem to have taken place in the Garden”.

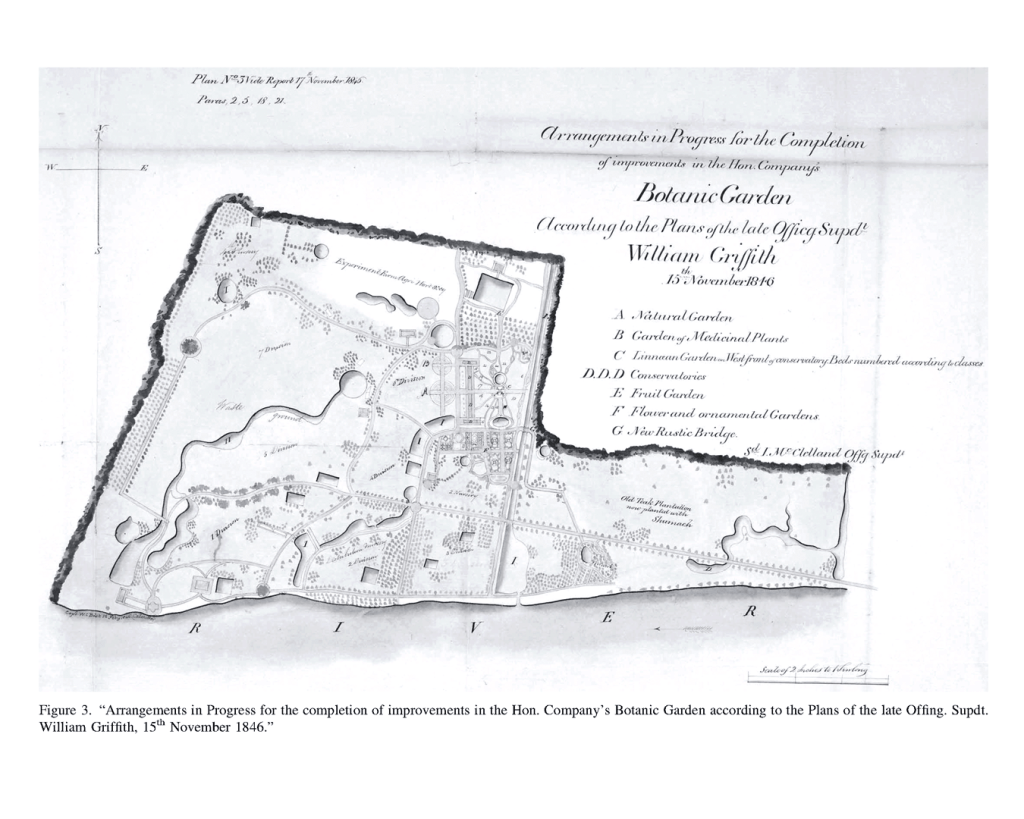

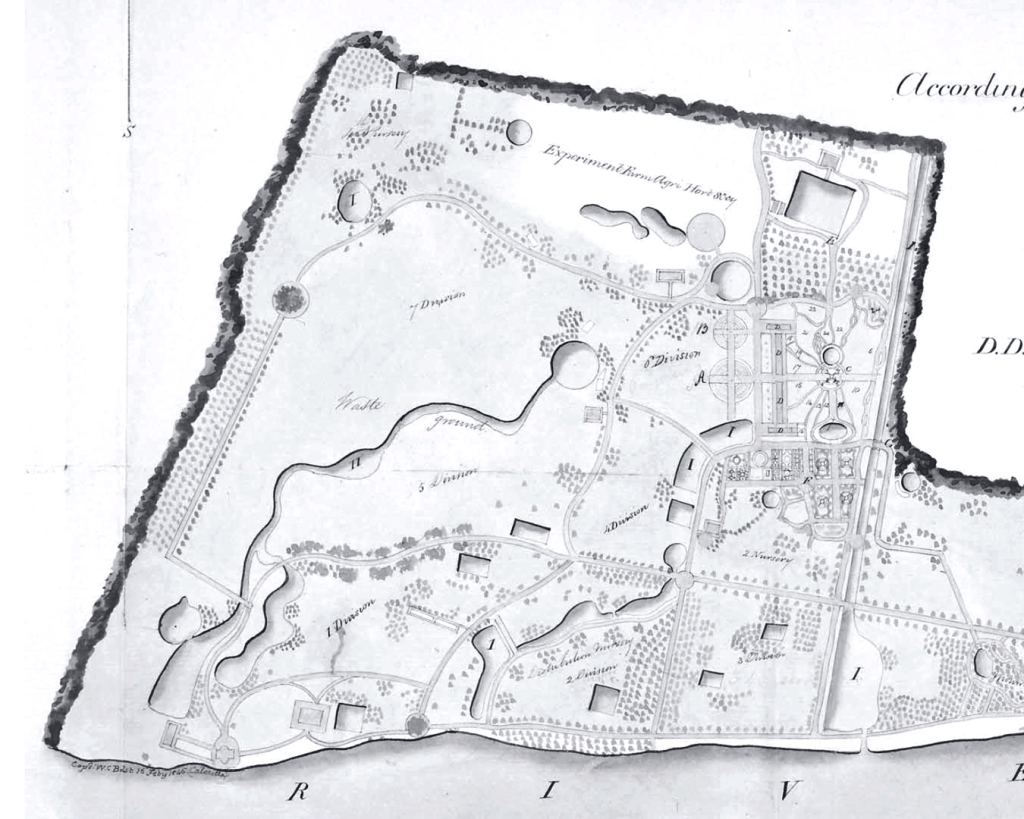

Among the first thing one notices about the third map (1846 map) is that the space occupied by the title is almost as big as the garden it introduces.

The intention here is to signpost the progress of the “improvements in the Hon. Company’s Botanic Garden” proposed by Griffith during his short spell in charge – a sharp contrast to his rival and senior Wallich. On taking control of the garden, Griffith described its neglected state. The garden was overgrown with trees, many of which were in poor condition; plants had been left unlabelled, and the library and the herbarium were a disordered mess. One section of Griffith’s 1844 report is subtitled “useless nature of many of the Books placed in the Library by Dr Wallich”

Griffith went on to compare the annual average of botanical drawings produced for the library during the term of superintendence of Dr Roxburgh and Dr Wallich:

“I beg to point out that if Dr Roxburgh’s average had been kept up and the drawings . . . kept in the Institution, the total number would have been 5622 instead of 3094”

The report made by Griffith for the Bengal Government was so critical of Wallich that when copies reached the East India Company’s Court of Directors in London they reacted by stating that it “contained strictures on Dr Wallich which ought not to have been circulated and which have therefore been struck out of the copies which we have distributed”.

What is interesting is that Griffith’s objections stemmed from more than simple personal animosity. The informal, casual layout of Wallich’s garden was offensive to Griffith’ conception of ordered rational science. He now proposed a radical reorganization of the garden, the completion of which would give it the same character as those Griffith rated the best in Europe: “viz: uniformity of design, adaptation of particular parts to particular purposes, including those of science and instruction”. The first victim of Griffith’s purge was “the ungarden-like mixture of herbaceous, shrubby plants of all sizes, and trees in the borders”. Griffith then determined, with reference to the objects of the institution,

“to form a series of separate Gardens, each having its own definite purpose”

Three scientific gardens were planned:

- the first illustrating Indian botany (“i.e. exclusively limited to Indian Plants, in which the Gardens are curiously deficient”)

- the second arranged according to “Natural Classification”

- and the third a Linnaean one “until these, especially the two first, are completed the Gardens will not be Botanic Gardens”.

In an attempt to render the garden “a botanical class book” its contents were organized into distinct compartments demonstrating systematic botany and the classification of plants. Writing several years later, Joseph Hooker described how “the avenue of Cycas trees (Cycas circinalis) once the admiration of all visitors . . . had been swept away by the same unsparing hand which had destroyed the teak, mahogany, clove, nutmeg and cinnamon groves”

Trees were felled and the flora borders flanking the paths were dug up while the only visible concession made by Griffith to aesthetic virtue was the creation of a “new rustic bridge”. The objective pursued by Griffith in his time as Acting Superintendent was to realign the layout of the Calcutta Botanic Garden so that it might conform to the shifts taking place in botanical science that had been promoted by colonial expansion.

At the time of Jones, Kyd, Hastings and Roxburgh, science as practised in India was not materially inferior or subordinate to the practice of science in London or any of the other European capitals. But Griffith and his contemporaries in the mid-nineteenth century embodied new scientific understandings that were born out of the global access that empire

increasingly provided.

Over the first half of the nineteenth century a hierarchical organization of knowledge becomes increasingly apparent, with the metropolitan centre asserting its superiority over the colonial periphery. Attempts to achieve global comprehension of physical phenomena necessarily abstracted them away from their specific geographical locations.

A shift in attitude – from seeking to understand and learn from India, to seeing it as a place lacking in civilized virtue and needing to be properly ordered – accompanied the centralization of scientific activity in the metropolis.

Wallich was by no means insulated from the changing scientific climate.

But it was Griffith who went much further in writing these changes into the landscape of the Calcutta Botanic Garden. The increased recognition of botany as a global rather than a local science informed the alterations that Griffith set about making. In his radical restructuring of the garden, plants were re-arranged according to both metropolitan scientific practice

and the priorities of imperialism.

Leave a comment